LocalMonero will be winding down

- Effective immediately, all new signups and ad postings are disabled;

- On May 14th, 2024, new trades will be disabled as well;

- After November 7th, 2024, the website will be taken down. Please reclaim any funds from your arbitration bond wallet prior to that date, otherwise the funds may be considered abandoned/forfeited.

How Monero Solved the Block Size Problem That Plagues Bitcoin

Note: It is highly recommended that the reader have read our articles "Why Monero Has A Tail Emission" and “Monero Mining: What Makes RandomX so Special”. This article builds off of the concepts presented in there.

Whenever individuals discuss the problems with blockchain, one of the first words to pop up will be 'scaling'. It's not a secret that blockchains don't scale well, but most people don't know why.

The truth is, scaling is actually an umbrella term that covers two different categories: Protocol support and technological support at a given point in time. In this article, we're going to focus our attention on one, Protocol support is basically a measure of how many transactions the protocol can handle at a given time.

Bitcoin has a block size limit, which means once enough transactions are included in a block, any additional transactions will have to wait in line for the next block. A helpful analogy would be thinking about a train. A train pulls up to the station, and those in line file in. Once the train is full, anyone left outside will have to wait for the next one.

Bitcoin uses fees to determine who gets into the block or not. Jumping back to the train analogy, one can imagine one potential passenger, that is about to be left behind, offers the train engineer five dollars to give him a seat. Other passengers follow suit, and eventually there is a bidding war to see who gets which seats. It's up to the driver to decide if he wants to honor the first-come-first-serve policy, but it's in his best financial interest to maximize his income by taking the highest bidders on board.

In this analogy, miners are the train drivers. They can include whatever transactions they want in the block, but they will generally choose the ones that have the highest paid fees.

Alternatively, if blocks are not very full, people have no incentive to pay high fees because there are plenty of free seats to spare.

In the height of the 2017 cryptocurrency boom, Bitcoin was flooded with transactions, and the fees skyrocketed for those that wanted to be included in the next block, or any near-future block for that matter. Those who were unwilling to pay high fees saw their transactions pushed back for hours, days, or even drop out of the queue altogether.

This was a harrowing insight into how Bitcoin would fare if the oft talked about ‘mass adoption’ were to occur. If Bitcoin was to be used by the masses, things would be even worse than in 2017, and Bitcoin would be inaccessible to anyone but the wealthy, simply because the throughput is small due to a fixed block size, causing the fee market to take over.

Monero foresaw this and wanted to do something different. So the Monero developers implemented a dynamic blocksize.

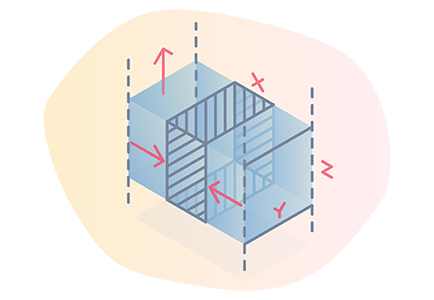

Basically, Monero also has a block size cap, but it’s a soft cap. When the line of waiting transactions gets too long, the miners can increase the size of the blocks. With our train analogy, you can imagine adding more train cars to fit the extra passengers. After the queue is empty the blocks shrink back to their original size going forward.

If this seems like a neat idea, it seems reasonable to ask why Monero is the only cryptocurrency that has implemented this. Why not add it on Bitcoin so as to put a stop to the throughput issues?

Unfortunately, this is not possible. There are several reasons why, and we’ll do our best to explain.

It's always in a miner's best interest to have large blocks. With large blocks they can fit in more transactions, and make more money off of the fees, as well as the block rewards. This has the potential to lead to spam attacks, where someone sends many small transactions, with small fees, to bloat the chain. Miner's would just raise the block size include them all because money is money, no matter how small. This would lead to consistently large blocks with little economic benefit. Bitcoin solves this by artificially restricting the block size, thereby generating a fee market. Spam attackers would have to outpay the other users in fees, and it is no longer cheap. But this means blocks get full leaving some transactions waiting as mentioned above.

So how can Monero have dynamic blocksizes but avoid spam attacks? The answer is simple, but clever. A penalty on the block reward is introduced when a block is bigger than normal. If a miner wants to increase the blocksize, the reward they get from finding that block will be less than they would otherwise receive. So they will only increase the blocksize when the paid transaction fees of the users outweigh the lost portion of the block reward. For example, if the miner would lose 0.5 XMR by raising the block size, and the sum of the paid transaction fees would be 0.4 XMR, then there would be a net loss of 0.1 XMR if they were to raise the size, so they wouldn’t do it. Conversely, if the total transaction fees added up to 0.7 XMR, then there would be a net gain of 0.2 XMR, even though they lose the 0.5 XMR from the block reward penalty, so the miner will increase the size.

These dynamic blocks, allow the network to grow organically, without aritifically restricting the blocksize to make a forced fee market, while still avoiding spam attacks. There are several more angles we can view this idea from, and more reasons why it wouldn't be possible to add to Bitcoin, but for now, we hope that the reader has an understanding of how Monero sidesteps several of the problems in Bitcoin and its derivatives, and how it plans to scale its throughput into the future.